|

Introduction

Depression Era Radical Novels

Depression Era Radical Plays

Depression Era Humor in Cartoons and Satire

Depression Era Novels about Displaced Farmers Published

before the Appearance of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath

SCRC Home

|

A

Selection of Depression Era Radical Plays

|

“Isn’t it a glorious thing to be able to say to bourgeois

Broadway: here, from the depths of our poverty, without your resources

of high-salaried stars, and publicity men, and hundred-thousand-dollar

budgets, and all the rest of the rhinestone-studded machine, working

against all the odds of class prejudice and the skepticism of bourgeois

critics, the struggling revolutionary theatre has matched you technically?”

(Michael Gold, “Stevedore,” New Masses 11, no. 5 [1 May 1934],

28). |

| “A dramatic high spot was the Theatre Guild’s production

of They Shall Not Die, John Wexley’s revolutionary drama of

the Scottsboro frame-up. The play ‘failed’ since its natural mass

audience—workers and students—were effectually barred by the customary

high Broadway admission scale. Had the Guild made special arrangements

with workers’ organizations, the play would have run for many more

weeks. They Shall Not Die was a powerful, well-built play,

as stirring an experience in the theatre as any play of recent years. |

|

|

But

the outstanding development of the season was the successful establishment

of the Theatre Union as a producing organization. Its first production,

Peace on Earth, a revolutionary anti-war play by George Sklar

and Albert Maltz, ran for sixteen weeks to an audience of over 125,000.

Its second production, the current Stevedore, Paul Peters’

and George Sklar’s play about the super-exploitation of Negro longshoremen

and the growing solidarity with their white fellow workers, seems

destined for an even longer run. We look forward to next season in

the expectation that the Theatre Union will give us not only revolutionary

drama but also revolutionary staging” (New Theatre [1 June

1934], 3). But

the outstanding development of the season was the successful establishment

of the Theatre Union as a producing organization. Its first production,

Peace on Earth, a revolutionary anti-war play by George Sklar

and Albert Maltz, ran for sixteen weeks to an audience of over 125,000.

Its second production, the current Stevedore, Paul Peters’

and George Sklar’s play about the super-exploitation of Negro longshoremen

and the growing solidarity with their white fellow workers, seems

destined for an even longer run. We look forward to next season in

the expectation that the Theatre Union will give us not only revolutionary

drama but also revolutionary staging” (New Theatre [1 June

1934], 3). |

|

“I was a radical once, a boy...a

fool of a boy — I murdered him, and he’s waiting round every corner

to murder me now” (John Howard Lawson, Success Story: A Play

[New York: Farrar and Rinehart, 1932], 212).

“Waiting for Lefty has been suppressed more

often than any other play in the history of the American Theatre.

|

“On January 6, 1935, an audience assembled at the Civic

Repertory Theatre in New York City for a New Theatre Night, witnessed

by the birth of a new era in American social drama, and the awakening

of a new singer. The play was Waiting for Lefty (winner of the

New Theatre–New Masses Play Contest) presented by the Group Theatre, and

the author was Clifford Odets. Even then, when the audience rose in their

seats and cheered until their throats were sore, no one realized fully

the widespread significance of this occasion. Today, Waiting for Lefty

is playing in twenty different cities from coast to coast, presented by

twenty different companies, to audiences ranging from the silk hats and

satin gowns of the Hollywood intelligentsia to the textile workers who

make those silks and satins in Paterson, New Jersey. Six months after

its downtown debut in New York City, the Group Theatre’s Broadway production

is still ‘packing them in’” (Alice Evans, “Waiting for Lefty,” New

Theatre [June 1935], 25).

| “The Federal Theatre is a pioneer theatre, because

it is part of a tremendous rethinking, redreaming, and rebuilding

of America....It...represent[s]

a new frontier in America, a frontier against disease, dirt, poverty,

illiteracy, unemployment, despair, and at the same time against selfishness,

special privilege and social apathy” (Hallie Flanagan, “Introduction,”

Federal Theatre Plays [New York: Random House, 1938], xii–xiii). |

|

|

“I don’t agree with Schwarz that protest is futile.

I think that every voice that is raised has its effect. My opinion

is that if you have convictions, you shouldn’t be afraid to express

them” (Elmer Price, We, the People: A Play in Twenty Scenes

[New York: Coward-McCann, 1933], 138). |

| “You know this mine ain’t owned by one man. Nossir!

It’s a company. Got five hundred mines if they got one. An’ do you

know where they’re shippin’ their coal? To their own steel mills!

An’ do you know how they’re shippin’ it? On their own railroads! You

can’t beat that, boy. You start at this company an’ pretty soon you

can find out who makes the laws an’ whose elects the Governor. An’

all I know is if you’re gonna be wantin’ your gravy you better stay

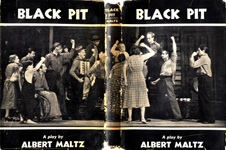

friends with the cook. Yessir!” (Albert Maltz, Black Pit [New

York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1935], 43). |

|

“A certain cleverness in striking a compromise between

the world about him and the world within has characterized the work of

the greatest as well as the least of successful playwrights, for they

must all take an audience with them if they are to continue to function.

Some may consider it blasphemy to state that this compromise must be a

considered and conscious act—will believe that the writer should look

in his heart and write—but in the theatre such an attitude leaves the

achievement entirely to chance, and a purely chance achievement is not

an artistic one” (Maxwell Anderson, Winterset: A Play in Three Acts

[Washington, D.C.: Anderson House, 1935], v).

|

“We have a law in this state, a viciously archaic and

outdated law, a law which makes human life of less value than stupid

rules of procedure written on the statute books. Once a man is adjudged

guilty and sentenced to death in the lower courts, and the judge of

the lower court has denied a motion for a new trial, no matter what

new evidence, new facts, may subsequently present themselves, no court—not

even the Supreme Court, can consider them” (I. J. Golden, Precedent:

A Play about Justice (New York: Farrar and Rinehart, c1931], 138). |

“The plays which reach the people are the plays which

the people not only understand but receive from; those plays from which

we illustrate our ideals, our imagination and our standards as to what

is vital and what is art. No play which is important artistically is removed

from life; it takes its very pattern and strength from the always active

powers of life” (Virgil Geddes, Left Turn for American Drama [Brookfield,

Conn.: Brookfield Players, 1934], 42).

|

New City, New York

October 12, 1940

Mr. Archer Huntington

1 East 89th Street

New York City

Dear Archer:

We had a wonderful first night and were on our

way to a success but the critics slapped us down very hard and we’re

still more or less horizontal.

Coming back to the road after it was all over we

found a great change in the landscape. The leaves had turned red

and gold, frost was in the air and the Huntingtons were gone. They

had drifted away like wood smoke leaving only rumors from Connecticut

way. My hat is only two years old but I shall certainly need a new

one soon. If you come back this way and have time for a little conversation

please let us know. We miss you.

Love to Anna and to you from Mab and me.

Sincerely,

Max

[Maxwell Anderson]

|

|

|